From Chaos to Context: Making Sense of Unstructured Data in Postgres

- Sudha Ravi

- Jan 12

- 5 min read

Why Regex? - A Smart Filter

Standard SQL search tools like LIKE or ILIKE as a simple "Ctrl+F" on your computer. They are great if you are looking for a specific word or a simple prefix, but they are clumsy when things get messy. For example, if you need to find every email address in a database, a simple search can't distinguish between a valid email format and a random string containing an "@" symbol.

This is where PostgreSQL Regular Expressions (POSIX) comes in. Regex is like giving your database a "smart filter" that understands patterns rather than just matching characters. Instead of just searching for text, you are teaching the database to recognize the shape of data—like a phone number, a postal code, emails, phone numbers, extract sub-strings, and replace complex patterns or a specific error code directly within the database. By using Regex directly inside Postgres, you can validate, extract, and even clean up complex data without ever having to pull it into a separate programming language. It’s a superpower for anyone who needs to make sense of unstructured information.

The Essential Postgres Regex Operators

Unlike other SQL dialects, Postgres uses a specific set of operators for Regex, Her are some reference guides listed below in the table.

1. Match Operators (The "How to Search")

The following operators are used in WHERE clause to test if a string matches a pattern.

2. Common Metacharacters (The "Pattern Logic")

These are the symbols used inside the string to define the “shape” of the data we are looking for.

As we know Postgres follows the POSIX standard, it is slightly different from “PCRE” (Perl Compatible) regex used in Python or JavaScript, as most of the common symbols listed above work exactly the same way.

Creating a Table with Messy Data

We are now going to create a sample table and populate it with “messy” log data that perfectly demonstrates why Regex is necessary.

Let’s see some real-world challenges and its solution.

Challenge A: Extracting user_id

Problem: Need to count users who had errors, but the user_id is hidden inside a text string.

Solution: We are using substring() with a capturing group to isolate the digits following user_id.

How it works

To understand the above query, we have to look at it through the eyes of the Postgres query planner. It doesn’t read the query from top to bottom; it follows a logical execution order.

Step 1: The Filter (The WHERE Clause)

Before doing any complex math or extraction, Postgres narrows down the rows.

log_level = 'ERROR' : It discards all 'INFO' and 'WARN' rows. This is efficient because it's a simple string comparison. filtered by log_level first. Simple equality checks are faster than Regex. By narrowing the data down first, we save CPU cycles.

message ~ 'user_id:\d+' : It then uses the Regex engine to look at the remaining messages. It only keeps rows where the text "user_id:" is followed by at least one digit (\d+).

Step 2: The Extraction (substring)

Now that Postgres has only the relevant error logs, it performs the "surgery."

substring(message from '...') : It scans the string for the pattern. By using WHERE message ~ 'user_id:\d+', we ensure that substring always finds what it's looking for. If we ran substring on a row without a user ID, it would return NULL, which might mess up our report.

The Capture Group (\d+) : Because the digits are inside parentheses, Postgres "captures" only that part. It ignores the literal user_id: prefix and just hands back the number (e.g., 1042).

Step 3: Aggregation (GROUP BY & COUNT)

Now that the database has a list of extracted IDs, it buckets them.

It sees two entries for 1042 and one entry for 8821.

It counts the occurrences in each bucket.

Step 4: Final Polish (ORDER BY)

Finally, it sorts the result set so the "noisiest" user (the one with the most errors) appears at the top.

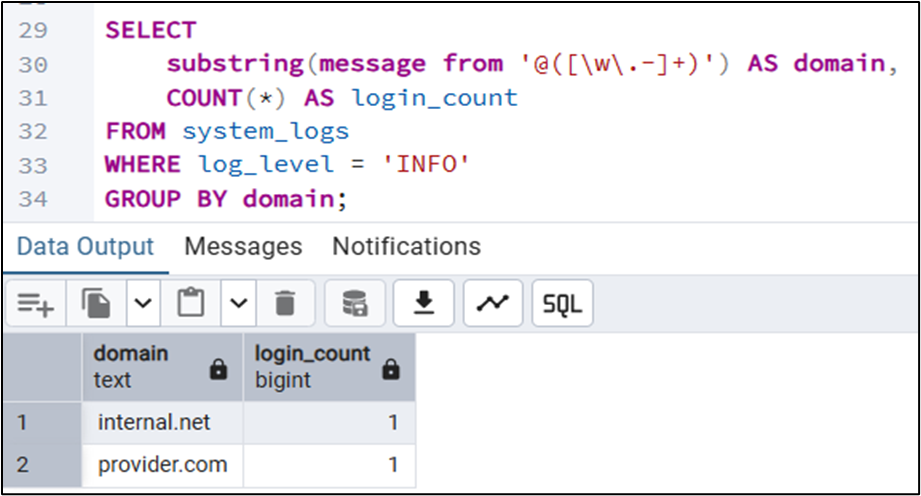

Challenge B: Domain Extractor

The Problem: The security team wants to know which email domains are accessing the system.

Solution: Point out which email providers are logging in frequently in the INFO logs.

How it works:

Step1: The Logical Flow

This query follows a "Filter → Extract → Aggregate" pipeline.

Filter (WHERE log_level = 'INFO'): Postgres first narrows the search to only "INFO" logs, as these are the rows containing login/logout events in our dataset.

Extract (substring): For each remaining row, Postgres looks for the @ symbol and grabs everything following it that looks like a domain name.

Group & Count: It takes those extracted domains (like provider. com and internal . net) and counts how many times each one appears.

Step2:Deconstructing the Pattern: @([\w\.-]+)

Let’s break down the regex pattern character-by-character :

@: This is a literal match. It tells Postgres: "Start looking exactly where the at-sign is."

( ... ): These are Capture Groups. They tell Postgres: "I need the whole pattern to find the right spot, but I only want to return the part inside these parentheses." (This excludes the @ from your final result).

[ ... ]: This is a Character Class. It defines a list of allowed characters.

\w: Any "word" character (A-Z, 0-9, and underscore).

\.: A literal dot (we use the backslash because a plain . usually means "any character").

-: A literal hyphen.

+: This is a Quantifier. It means "match one or more" of the allowed characters. It keeps grabbing characters until it hits a space, a comma, or the end of the string.

Challenge C: String to Numeric Conversion

Problem: To calculate average latency.

Solution: convert the logs mentioned in ms to a integer(numeric) to calculate the average latency.

How it works:

How it Executes

The Filter (WHERE message ~ '\d+ms'): It looks for any row where a digit (\d) is followed by the letters "ms". This ensures we don't try to perform math on rows that don't have a latency value, which would throw an error.

The Extraction (substring): It finds the pattern, but because of the capture group (\d+), it ignores the "ms" and only pulls out the raw digits (e.g., it turns "1250ms" into the string "1250").

The Cast (::INTEGER): This is the critical step. It converts the extracted string "1250" into a real mathematical integer 1250.

The Aggregation (AVG): Once it has a list of integers, it calculates the mathematical average.

2. Breaking the Regex: '(\d+)ms'

Breaking this down character-by-character helps your readers understand the "why":

( ... ) (The Capture Group): This tells Postgres: "Look for the digits and the 'ms', but only keep the digits."

\d: Matches any digit from 0 to 9.

+: Matches one or more. This ensures it catches 5ms, 50ms, or 5000ms.

ms: A literal match. It acts as an "anchor" so Postgres knows exactly which numbers represent milliseconds and not a User ID or an IP address.

Performance: The "Hidden" Cost of Regex

Regular expressions are powerful but CPU-intensive. If you run a ~ query on 10 million rows, Postgres will perform a "Full Table Scan," which is slow.

The Solution: Trigram Indexing By using the pg_trgm extension, Postgres breaks your strings into 3-character "trigrams," allowing it to index patterns.

Conclusion:

We began with a table of messy, unstructured logs and transformed it into a source of actionable intelligence. Through the power of PostgreSQL POSIX Regular Expressions, we’ve seen that you don't need complex external scripts to parse your data—the database is already equipped to do the heavy lifting.

By mastering these three pillars, you’ve upgraded your SQL toolkit:

Precision Extraction: Using substring () with capture groups to pull specific metrics out of strings.

Data Integrity: Using WHERE clauses as a safety net to ensure your regex matches before casting to numbers.

Production Readiness: Implementing pg_trgm indexes to ensure your queries remain fast even as your data grows to millions of rows.

Regex is often intimidating, but in a database context, it is the bridge between "dark data" and clear insights.